No one doubts that China's dramatic growth spurt over the past 4 years has been the driving force that has pushed commodity prices higher. Even though the Chinese economy is still going at full blast (industrial output is growing 16% yoy), past experience has taught us that there are limits to how much commodity prices can go up.

For one, with higher prices there are more incentives to ramp up production. In addition, price increases blunt demand, as buyers turn to cheaper alternatives (for example, according to INCO, the nickel content of stainless steel has fallen in response to higher prices for this metal).

The market for copper offers a great example of how these forces work, sometimes in a very odd fashion.

While Chinese copper demand has remained robust, in the industrialized nations it has plunged this year due to high prices, leading to an overall drop in world consumption of 1.4%, according to this forecast. According to the IMF, copper prices rose 43% last year and 38% in 2003.

Yet, despite the fact that refined supply is forecast to grow 3.1% this year, prices have risen an additional 36% (up to November).

What gives? Well, in 2003 and 2004 demand --driven by China and other emerging economies--far outstripped supply, depleting existing stocks. With latent demand very strong, the market has needed dramatic price hikes to partially close the demand-supply gap.

Obviously, it's hard to ramp up the production of minerals in the short run. But eventually market incentives lead to the expected response: in 2006, the ICSG forecasts that supply will rise 8%, surpassing demand for the first time in 3 years (although prices will likely stay high while inventories are built back up)

Wednesday, December 14, 2005

The red economy and the red metal

Posted by

Andrés

at

4:41 PM

|

![]()

Sunday, December 04, 2005

Moving on to football

Don't miss this article by Michael Lewis on how a coach of a minor Texas university is turning football (or American ovoid handball, as a tetchy friend would have it)strategy on its head. Basically, it involves a pass-heavy approach that seeks to stretch the field as much as possible, both horizontally and vertically.

This is definately the wave of the future. Besides the violence, what I really lack about football is that it has a much larger strategic component compared to other sports. Alas, the sad fact is that most NFL coaches stick to very conventional/conservative playcalling, wasting the potential to achieve victory through greater creativity and flexibility (with some partial exceptions, such as the Patriots, Eagles and, until recently, the Rams).

This is not precisely a new idea. Bob Oates, who writes for the LA Times, has consistently favored this approach.

By the way, if you like football, go visit Football Outsiders if you haven't done so already. Aaron Schatz and his crew are doing a great job by applying statistical modelling to evaluate performance on the gridiron. It simply is a must read, although I do hope that in the future they'll also include --to the extent possible--on the impact of stategy.

Posted by

Andrés

at

1:36 AM

|

![]()

The manufacturing rat race

Last week, Brad DeLong speculated that one of the reasons that U.S. auto manufacturers faced such daunting legacy costs was that the wages and benefits paid to their employees reflected the expectation of maintaining oligopolistic profits.

I don't know that much about the auto industry, but I reckon that if those profits existed, they couldn't have lasted much beyond the 1970's.

But, in any case, the auto industry does illustrate the degree to which even a relatively sheltered industry (in terms of barriers to entry) is a rat race.

Taking some BLS data, I found that new cars today cost around 60% less in inflation and quality adjusted terms than they did in 1953 (the first year with data). This number is in line with the trend observed for durable goods as a whole.

This basically means that you face constant pressure to become more efficient or develop some type of competitive advantage to protect your pricing (such as better design or some other form of strong intellectual property). Obviously, U.S. car producers haven't kept up, at least with their Japanese counterparts, event though they've surely made huge gains in productivity over the last few decades.

Posted by

Andrés

at

12:31 AM

|

![]()

Friday, December 02, 2005

Foreign policy amnesia

Why does the U.S. never learn from its foreign policy mistakes? I can't find a good answer. But to my horror they just keep coming. As if the Irak debacle weren't enough, the idea of treating Mexicans as the Israelis treat the Palestinians is gaining ground.

Let's start with President Bush's big speech this week, in which he laid out (again) his plan to deal with the large flow of illegal immigrants to the U.S.

The President's proposal --a hybrid guest-worker programme that includes the possibility of obtaining citizenship, but also contemplates measures to crack down on illegal immigration---sounds fairly sensible. Nonetheless, it is, as expected, very flawed and it faces substantial opposition from his own party. As a result, it's fairly likely that something far worse than the President's proposal will be enacted.

Why is it flawed? Simple. It assumes that the U.S. can --by itself--fully regulate the flow of immigrants.

Bush's plan aims to admit "enough" workers to satisfy the needs of its farmers and firms while keeping out all others who wish to come by cracking down on the employment of illegals and stepping up security on the Mexico-U.S. border.

Let's start with Economics 101. There is a huge, huge number of people willing to come and work in the U.S. There is no way the U.S. will allow all of them to come, even if there are enough jobs available. In other workds, supply will always exceed (artificially regulated) demand. Hence, the proposal's mechanisms to limit supply.

Will they work? Not likely. As the President himself admits, the greatly increased spending on border security has not made a dent on the flow of immigrants. There is no reason to believe that further spending, short of building a 2,000 mile Israeli-style wall on the border and massive deportations.

Such a wall would, undoubtedly, reduce the flow (but not stop it, by far). But just think for a second about the symbolism (let alone the expense). It would mean that the U.S. is turning its back --literally--on Mexico and the rest of Latin America. (Am I exaggerating? Just read what the people who want to build such a wall say).

Let that sink in. In a world where the U.S. has few friends, it will work to alienate (even more) a region to which it already has significant cultural, economic and ethnic ties.

Is there a better way? Yes. Actually, a very simple way: be more generous. The U.S. provides its "friends" in the Middle East (Egypt, Israel, Jordan) more foreign aid in one day than it has ever given to Mexico. Why not propose a bold development partnership to Mexico and Central America? Sure, it would cost money, but probably no more than the cost of fences and the like. It would engender goodwill and reduce immmigration in the long-run. And it would give the U.S. a lever to push for reforms in Mexico.

A guest-worker programme should be established, but it will only be a net positive if it is realistic (for example, it actually deals with issues such as the workers' families). And, yes, the U.S. whould have more control in areas such as employment.

Sadly, there is little or no chance of something like this happening. Bush never even mentioned talking to Mexico in his speech and the fence-builders don't give a damn about anything south of the border. The only hope I have is that the American people at least seem to recoil at some of the nastier policy options in this area.

Posted by

Andrés

at

3:41 PM

|

![]()

Tuesday, November 29, 2005

Legacy costs

By now, we all know that most nations face a nasty pension crisis in the not so distant future. For some corporations, like GM, that future is now. Yet, it is hard to find creative and serious policy debates on how to tackle this huge problem.

Sure, many people have put forward what can only be called the "Scrooge" alternative: longer working lives and/or lower benefits. These may (specially the former) have some merit, but they do seem rather unfair, notably to older workers.

In the case of firms facing bankruptcy, the solution (at least in the U.S.) has been fobbing off pension liabilities to the government's Pension Benefit Guarranty Corp., which takes over the pension plan (but has no claim on the sponsoring firm's assets). For many firms --take Delphi as a good example--the ability to ditch pension liabilities is very attractive. Unless the system is reformed, this trend threatens to snowball massively (the government already projects that the PBGC's deficit at over 100 billion dollars).

I want to make it clear that many firms have to go under and eliminate liabilities such as these to survive. After all, large pension deficits increase borrowing costs and restrict borrowing facilities, besides making labor relations very tense.

For this reason, I'm very pleased that Dick Berner of Morgan Stanley has put forward a serious proposal to deal with this problem. It basically involves having the PBGC fund the outstanding net pension liabilities in exchange for having the firm cover this cost (with interest) over a certain period of time. It would also give the PBGC priority over other creditors and force firms to fully fund new pension/retirement promises.

I like this idea, which (as noted by the author) has parallels in the S&L bailout and, to a degree, on the Brady-bond restructuring of Third World debt. While these plans involve upfront costs for society--no getting around that--they work quite well in the long-run.

However, I do believe it doesn't go far enough. For one, it doesn't address a very big issue: firms with large pension liabilities are often badly managed and also need to reduce current labor costs. This calls for greater involvement of workers in corporate governance, as Brad De Long has pointed out, perhaps through equity-for-concesions swaps. This sounds fairly obvious, but they don't seem to have worked well in the airline industry (I don't know the details too well).

Posted by

Andrés

at

5:40 PM

|

![]()

Friday, November 18, 2005

What the hell are the markets thinking?

After months of denial, yesterday I finally accepted a very basic point: I can’t explain anything anymore.

To do my job, I need to develop a good idea of global economics and politics and how they translate into asset prices in order to develop successful investment strategies. But right now I see a breakdown between “objective” reality and its reflection in the Matrix-like world of financial markets.

This may sound extreme, but bear with me. At first glance, things are not going badly. The world economy is growing at a very good rate and it has proved very resilient to the recent shock in energy and commodity prices. As a result, stock markets the world over are doing great and long-term interest rates are still at or near the lowest levels in decades.

Yet, the political superstructure on which economic prosperity depends is crumbling.

The United States is, for all practical purposes, does not have a functional government. I say this with amazement, dismay and consternation. George Bush has lost even the limited grasp of reality he had and has no idea how to correct his past mistakes, which are rapidly eroding his authority, let alone set a coherent policy agenda. The less we can say about his second in command, the better. And let’s not forget that his party is in disarray, while the opposition does not have the standing, intelligence or leadership to defend the nation’s vital interests.

And we have three more years of this to look forward to.

Looking abroad, things are not much better. Western Europe’s heads of state are discredited (Chirac, Berlusconi and now, to some extent, Blair) or inexperienced (i.e. Merkel). Japan’s Koizumi seems like a strong leader, but he leads a timid nation. Russia is ruled by a thug and China has still not developed a strong, effective voice in international affairs.

In addition, many of the world’s leading multilateral organizations, such as the U.N., the World Bank and the WTO, seem paralyzed or ineffectual.

Basically, this implies that if a crisis that requires effective coordination arises, we probably won’t get it, with predictably negative consequences.

Yet, the bond market isn’t worried one bit: risk spreads are actually below the average of the past 15 years (the BAA/10 yr-Treasury stands at 184 basis points, vs. an average of 208 basis points). Stocks are rising and emerging market assets are once again in full bloom.

Even if the probability of a nasty, unforeseen crisis is very low, the damage would be severe given the above conditions. My impression is that asset prices are not pricing this in.

Why? I have no idea.

Oh, and have I mentioned that GM is about to go bankrupt? Even though this firm is a shadow of its former self, it is still huge by any measure except market value. When a CEO writes to all employees to categorically state that the firm won’t go bankrupt, a Chapter 11 filing is a sure thing (unless the aforementioned CEO is quickly fired and replaced by someone who can act correctly and decisively).

Posted by

Andrés

at

4:11 PM

|

![]()

Wednesday, November 16, 2005

Evangelical Economics

Say it ain't so! But, yes, economics can be put to use to promote the aims of religious conservatives.

Marginal Revolution offers this example: a study that finds that teenage girls engage in less risky sex if the "cost" of abortions is raised by the adoption of parental notification laws.

Since reducing risky sex by making abortion costlier is also associated with lower rates of teenage pregnancy and STI, the authors clearly approve of parental notification laws.

Indeed, the authors do discover the very obvious point that teenagers do respond to incentives. In fact, using their logic, why don't we go all the way and make abortion illegal again?

I'm not getting into THAT argument. I just want to make the obvious point that there are other, more effective, ways of reducing the incidence of STI's/pregnancy among teenagers: mandatory, realistic and rigorous sexual education and easy access to contraceptives. Áfter all, this works fine in Western Europe, where abortion and teenage pregnancy rates are orders of magnitude lower than in the United States.

Yet, this alternative ignored, both by the authors and by politicians, even though it's more humane than the return to the days of coathanger abortions.

But that's exactly the problem with fundamentalists. They can't distinguish between sinful behavior. In other words, to them fornication is just as bad as murder.

Hence, they'll resist making contraceptives more accesible to teenagers and proving them with decent sex-ed, even though that would probably make abortion much rarer than straight prohibition ever could. Hence, they oppose making emergency contraception available over the counter. Hence, they oppose a vaccine against the sexually-transmitted HP virus that kills thousands of women each year.

In a way, these people are just as vile as their Islamic cousins.

Posted by

Andrés

at

1:57 PM

|

![]()

Thursday, November 03, 2005

Baseball and hateful partisans

Yes, nothing gets my goat more than blinkered ideologues of any stripe, be they politicians, artists or journalists. I also have my principles and prejudices, but I do try to keep my mind open and my facts straight.

Forgive me for blowing off some steam, but this article made my head boil. Yes, it's from the Nation, a decidedly left-wing magazine. However, this is no excuse for doing lousy journalism.

The author slams pro U.S. baseball teams who run academies for talented Dominican kids for luring with promises of fame and riches, only to leave most of them penniless and without an education.

Yet, he never really talks to anyone directly involved: the managers of these baseball academies, the kids living there or their parents. Curiously, he never even investigates or actually affirms in black and white that the academies don't provide any education, while admitting that they do provide decent room and board and benefits such as English lessons.

It gets worse. If nearly all or even most Dominican kids had decent educational opportunities, the author's main premise might have made sense. After all, the expected lifetime income of a high school graduate is probably higher than the expected income of a person who drops out of school to pursue the 1/1000 chance of becoming a pro baseball player. However, most Dominican kids don't have that opportunity. According to UNESCO, only 31% of Dominican boys are enrolled in secondary schools (probably of very poor quality).

Given this grim reality, attending a baseball academy is probably the best rational choice for these kids. Not that we'll ever know form journalistic merde such as this piece.

Posted by

Andrés

at

4:42 PM

|

![]()

Back again

Sorry for disappearing for a few months. The aliens conclded in the end that I was one sorry human specimen and decided that no further testing was necessary. So, given that I'll stay earthbound, might as well keep up the ol'blog. Thanks for stopping by.

Posted by

Andrés

at

4:38 PM

|

![]()

Thursday, July 21, 2005

Dumb headline of the day

Well, it's actually from yesterdary, but never mind. As seen on FT.com: "Wall Street bounces back after GM disappointment"

Ask yourself what is wrong with that statement (yes, GM did report below the consensus earnings forecast). If your answered that it's impossible for GM to dissapoint, no matter what the consensus expectations are, go buy yourself a cigar. After all, it has lost market share for nearly as long as I've been alive. It's management, who has tried any number of strategies to turn things around (except maybe human sacrifice to ask the gods to jinx Toyota), gives new meaning to "hapless". It'd be broke if it weren't for America's inexplicable love of big, ugly trucks.

In related news, it takes a brave (or foolhardy) soul to forsake a cushy Wall Street post to join GM. Wild conspiracy theory: he knows the current management team will probably be run out of town sooner rather than later by Kerkorian and could emerge as a credible candidate for a top job.

Posted by

Andrés

at

7:13 PM

|

![]()

Friday, July 01, 2005

The U.S. as a gigantic hedge fund

Yesterday, the Bureau of Economic Analysis reported that the net international position of the U.S. –which is the amount of U.S.-owned assets abroad minus the amount of U.S. assets held by foreigners--was minus 2,484.2 billion dollars at yearend 2004, higher than the minus 2,156.7 billion level in 2003 (figures at market value).

At the end of 2004, Americans owned nearly 10 trillion dollars worth of foreign assets, while foreigners owned U.S. assets worth 12.5 trillion dollars.

This comes as no surprise. After all, the U.S. has been running current account deficits (i.e. has been a net barrower) for a long time.

The real shock comes when one sees the returns earned by these assets held by each party. According to the latest balance of payments data, the income earned by U.S.-owned assets in 2004 was equivalent to 4.5% of yearend assets at market value, while foreigner earned just 3.2% on their American assets.

That’s not all. The BEA breaks down the changes in value of assets price appreciation, foreign exchange gains and others by source (price appreciation, foreign exchange gains and others). Assets owned by Americans appreciated 5% in 2004 (before taking into account foreign exchange gains/losses and with yearend 2003 values as the base level). Foreign-owned U.S. assets gained only 2.7%.

As a result, U.S.-held assets gained 9.7% (price appreciation + income), while foreigners gained 5.8%. Obviously, by taking yearend 2003 assets, these returns are somewhat overstated, but still indicative.

Why are U.S.-owned assets more profitable? The answer composition of the assets. In first place, 97% of the assets held by Americans are privately held, a percentage that falls to 84% in the case of foreigners (the remaining 16% is held by governments and official institutions such as central banks). One would expect privately held assets to yield higher returns.

But there are significant differences even in private assets. In the case of U.S.-owned assets, holdings of equity, either as foreign direct investment or foreign stocks, were 60% of the total in 2004, while foreigners held only 45% of their private assets in these two categories. In general, equities should also yield higher returns, although their risk is also higher.

So, in a way, the U.S. borrows short to lend/finance long. If it weren’t for the sheer scale of its borrowing, it’s actually a pretty smart strategy that plays to America’s comparative advantage in finance.

Brad DeLong links to a study that takes a deeper look at this phenomenon. Interestingly, the U.S. earns more even within specific asset classes.

Posted by

Andrés

at

4:02 PM

|

![]()

Wednesday, June 29, 2005

Climate change is for real

As a science dunce who has trouble telling his electrons form his photons, I'm not qualified to disucuss the debate concerning global warming. But when insurers --more concerned with odds rather than politics--express their worries in public, it's a sure sign that it's for real.

Posted by

Andrés

at

9:11 AM

|

![]()

Friday, June 24, 2005

A very vicious circle

The Buttonwood column at The Economist lays it out very cleary.

Companies and asset managers have tended to take a laid-back approach to pension underfunding, relying on the markets to right things as they often have before. What is worrying about the latest numbers is that we are seeing them towards the end of a period of strong economic growth and corporate profitability, neither of which is likely to continue. John Mauldin, an investment consultant, calculated in a recent column that total portfolio returns over the next ten years were likely to be around 5%, far less than the 8-9% projected by most funds. He reckoned that the total shortfall in America could be somewhere between $500 billion and $750 billion. And that is without counting companies’ promises to provide health care to employees and retired workers. Nicholas Colas at Rochdale Research, an independent firm, calls these obligations a bigger problem than pensions because they are neither funded nor insured.

There are a couple of weird circularities here. Most of the burden of filling these gaps will fall on the companies themselves, which will depress their profits. That, in turn, will depress share prices, which will make it harder to achieve adequate investment returns. And if asset managers turn en masse to bonds with long maturities to match their assets and liabilities more precisely, which is necessary especially for older plans, that will raise bond prices, depress bond yields and increase the present value of assets they must hold—again, widening the pensions gap. They could, of course, look to other asset classes that pay higher or “absolute” returns (hedge funds of funds, private equity, property) and many are doing so. But “alternative” assets do not typically account for more than one-tenth of the total portfolio, in part because they are labour-intensive to manage.

A the column spells out, there is a huge funding gap and no one –firms, workers, taxpayers, shareholders—wants to end up holding this hot potato.

I’m not an expert on this subject, but I believe it’s likely that that the burden will fall on the weakest link: shareholders, who as always have the largest collective action problem. How so? Well, one solution will be to “capitalize” the pension obligations by swapping the funding obligations for shares. This basically implies, for example, that the United Auto Workers will end up owning General Motors and Ford.

Maybe this is a non-starter under conditions in the United States. But I believe this “solution” is feasible in may contexts. For example, most state-owned firms in emerging economies have pension deficits that make the funding gap in the U.S. or other developed nations look like child’s play. Governments are often very eager to privatize those firms to avoid the inevitable rescue package that will bust the treasury, but unions are adamantly opposed. So, in the end, the likeliest bargain will be to transfer ownership to the workers.

Posted by

Andrés

at

11:05 AM

|

![]()

Tuesday, June 21, 2005

Oil gone wild

It’s rather remarkable how the markets have reacted to oil at nearly 60 dollars per barrel, just four weeks after dropping to 47 dollars per barrel: stock prices have risen on average and bond yields have stayed put.

The good news is that high and rising oil prices are usually a sign of strong growth in the world economy, which of course is most welcome.

The bad news is that we’re entering dangerous territory and no one seems to know what’s really going on.

Some analysts, such as Andy Xie over at Morgan Stanley, explain away the jump in oil prices as the consequence of rampant “speculation”. They argue that slower growth and the rising output of petroleum substitutes will cause a dramatic collapse in oil prices in the near future.

Obviously, “speculation” is an oft misused and abused word, but there’s some evidence to back this point of view. For one, it’s hard to reconcile oil at record price levels with inventories at 5-year highs in the U.S.. And let’s not forget that neither the demand or supply outlook has changed over the last few weeks.

Yet, the fact remains that spare capacity is low and demand in the U.S. and the Asia Pacific region is still very strong. (By the way, I don’t buy the capacity-constraints-at-refineries argument: heavy crudes have risen as much in value as light crudes).

Things get even weirder at a more fundamental level. While many insist that oil production will keep on rising for quite a while, the “peak oil” movement loudly argues otherwise.

Regardless of who’s right, one has to wonder what impact energy prices at this level will have on the world economy. Sure, it’s dodged the bullet so far, but it’s possible if that the price of oil crosses-a certain threshold—obviously unknown—the impact will be severe.

Where does that leave mere mortals like me? Well, if I have to trust anyone, it’d be the price mechanism, which is signaling strong demand and high prices for the foreseeable future. However, for investment purposes, I’d use fairly conservative assumptions: my long-term guess is that oil will average around 40 dollars per barrel over the next few years. And, yes, high prices will take their toll on output over the next few months.

Posted by

Andrés

at

2:48 PM

|

![]()

Thursday, June 16, 2005

Bin travelin'

Sorry for not posting, but I've been travelling a bit in the U.S. on business. As always, it's a pleasure to be here (Southern California), although the weather has not been very cooperative (cloudy and cool).

With a patchy net connection, I've indulged in watching local TV. All the advertising by lawyers never ceases to amaze me or any other foreigner for that matter. According to this article, it totals around 500 million a year, most of it spent on television. That's about 499 million more than lawyers spend in the rest of the world.

And speaking of being overlawyered, on a visit to a residential compound I asked an employee what kind of people lived there (I was thinking along the lines of singles/married couples with kids). With a straight face, he stated that he couldn't answer for legal reasons (apparently some sort of non-discrimination statute).

Yet, you can find very, very detailed data that breaks down enrollment by ethnic/racial group and their respective standarized test scores.

So, you can't ask about what neighbors you'll have (something you can easily find out just by hanging out a while), but you can precisely tell who your children will study with. That's weird and wonderful America for you.

Posted by

Andrés

at

3:32 AM

|

![]()

Saturday, June 11, 2005

Anarchy and cell phones

The emerging nations of this world are a strange mixture of pockets of modernity and large areas of abject poverty. This sets the stage for some truly amazing, heartbreaking stories. Take this one from the latest issue of The Economist:

Veronique, an office worker, was separated from her daughter by the war. When peace broke out, she booked an aeroplane ticket for her (penniless) girl to rejoin her. But before the daughter could board the plane, she was detained. Her yellow fever vaccination card had been stamped by rebel health authorities, and so was invalid, the officials tut-tutted. Alas, she had no money for a bribe.

But Veronique was able to send her the equivalent of cash by mobile telephone. She bought $20 worth of telephone cards. These give you a code number which you key into your phone and thereby “recharge” it with pre-paid airtime. Veronique called the obstructive officials and gave them her code numbers to recharge their own mobile phones. It took only minutes to send her bribe across the country—faster than a bank transfer, which would in any case have been impossible, since there is no proper banking system.

That's Congo. Private cellphone networks and private airlines work because the landlines do not and the bush has eaten the roads. Public servants serve mostly to make life difficult for the public, in the hope of squeezing some cash out of them. Congo is a police state, but without the benefits. The police have unchecked powers, but provide little security. Your correspondent needed three separate permits to visit the railway station in Kinshasa, where he was stopped and questioned six times in 45 minutes. Yet he found that all the seats, windows and light fixtures had been stolen from the trains.

If only Joseph Conrad were alive today.

The Congo is obviously an extreme, tragic case. But even for more "developed" emerging nations, true prosperity and stability remain elusive, even nearly 200 years after independence, as is the case of Latin America. Just look at Bolivia. I don't want to be a pessimist, but even well-meaning initiatives such as debt relief are not going to make a real difference unless the politics of the these countries can be fixed.

Posted by

Andrés

at

6:43 PM

|

![]()

Thursday, June 09, 2005

Forecasting stocks

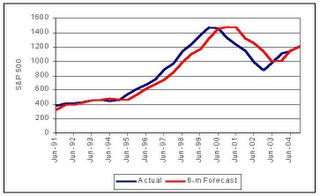

Yesterday I posted about the results of the Livingston Survey regarding the economic outlook for the U.S. I was surprised to find that the survey participants are also asked to forecast for the level of the S&P 500 for periods ranging up to 24 months ahead.

So, are economists any better than others at forecasting the stock market? Not really.

Due to data comparison problems, I only took a look at 6 and 12-month forecasts from 1990 onwards. The results are pretty clear, as can be seen in this graph:

Economists commit the same sin as the average investor: their forecasts are basically just extrapolations of recent trends. And even in periods where there were clear trends, these extrapolations were wide off the mark. For example, the level of stock prices was consistently underestimated in the 1990’s (not surprising given the bubble and their knowledge of long-term trends).

On average, there was a +/- 15% error margin for 6-month forecasts, which rose to +/- 20% in the 12–month horizon.

If you had trusted them to manage your money, say by allocating between stocks and bonds, you would’ve had terrible results. That’s perhaps the reason that on Wall Street economists are mostly confined to the safety of research departments.

Posted by

Andrés

at

12:09 PM

|

![]()

Wednesday, June 08, 2005

Want to know what economists are thinking?

Just go and check out the results of the Livingston Survey, the oldest continous survey of U.S. economic forecasts (in business since 1946). Reuters has a good summary here.

The results are very similar to the ones I described a few days ago (based on a Federal Reserve survey): growth will stay over 3% and inflation will average 2.5% over the next ten years. Thus, economists see long-term interest rates rising to 5% as early as next year.

Needless to say, the bond market begs to differ. Only time will tell who's right.

Posted by

Andrés

at

7:32 PM

|

![]()

Of spreads and stocks

As if the long-term rate conundrum weren’t enough, I’m afraid we have another puzzle on our hands, this time related to the behavior of bond spreads and stock prices.

Spreads –in this case the difference between the yields of Baa-rated bonds and 10-year Treasuries--are usually high during recessions or periods of slow growth and tend to fall in more prosperous times. They aren’t correlated with the level of rates, but they do show a strong negative response to changes in rates: that is, spreads rise when rates fall and vice versa. The cause is clear: falling rates imply lower expected inflation, which in turn reflects slower growth in the economy and a lower earnings performance in firms.

The following graph shows normalized (i.e. long term average =1) 10-year yields and Baa spreads.

img src="http://photos1.blogger.com/img/31/6194/320/spreads.jpg">.

A few brief observations:

· After 2000, spreads went wild, reaching never before seen heights despite the fact that the 2001 recession was pretty mild. This probably reflects structurally higher leverage.

· Despite robust economic growth in 2004/2005, spreads are still pretty high relative to the long run average.

· As was to be expected, spreads have risen sharply in the past few weeks, in tandem with falling long-term rates.

· Spreads will only fall to long-term average levels if rates rise towards 5%.

The central message here is that the recent fall in rates is not good news, as it signals a weaker economy that will lower credit quality and raise the level of financial risk.

However, it’s worth noting that stocks in the U.S. have posted gains in the last two months, a period in which spreads rose sharply. Needless to say, this is contradictory: stocks usually move in the opposite direction of spreads.

So who’s right? I honestly wished I did. The only thing I do know is that we live in very uncertain times when traditional correlations are not working as expected. Hence, I’d have a very cautious investment policy. Cash anyone?

Posted by

Andrés

at

11:32 AM

|

![]()

Tuesday, June 07, 2005

Reading the Fed's tea leaves

Like the Kremlinologists of yore, central bank watchers are always tempted to read between the lines and derive meaning from seemingly inconsequential remarks. Well, at least that's how I feel today. It seems everyone else (see here) is reading Greenspan's remarks in a different light than yours truly. I believe he might be signalling that short and long term rates were bound to rise in the none-too-distant-future, while others see these comments as a sign that rates will be low for quite some time.

We'll know more soon, as Greenspan is set to testify before Congress later this week.

Posted by

Andrés

at

10:46 AM

|

![]()

Monday, June 06, 2005

Does Greenspan have a hidden agenda?

Alan Greenspan is still puzzled by the low level of long-term interest rates. In these remarks, published today, he goes over some of the hypotheses commonly mentioned: pension fund adjustments, Asian central bank purchases of U.S. bonds, expectations of an economic downturn and lower inflation expectations due to globalization. He finds them all wanting.

So, believe it or not, the world's foremost central banker doesn't know what factors are driving long-term rates lower. It seems rather absurd. He could've at least had the decency of offering his own ideas. This, in its way, is both revealing and suggestive.

My guess is that he's singalling in a very subtle way that long-term rates should be higher. I can think of two reasons (non-exclusive) for this.

First of all, given last Friday's weak employment numbers, many investors are expecting that short-term rates won't rise much more, if at all. If the Fed surprises by hiking them --or signalling to that end--more than expected, then all those people buying 10-year Treasuries at 3.9% are in for a very nasty shock, which may create instability (1994 all over again, only with a lot more leverage).

This scenario is not far-fetched. Richard Berner of Morgan Stanley argues here that the markets are underestimating the economy's strength and the that inflation will keep rising. He sees the Federal funds rate rising to 4%.

Alternatively, Greenspan may like rates to be higher to dampen some of the economy's flashpoints: the huge current account deficit, the real estate froth/bubble, some of the wilder hedge funds, etc. To a lesser or greater extent, all pose a significant risk.

If long-term rates don't rise significantly over the next few weeks, it's likely that the Maestro will be more explicit, perhaps even offering 'tentative' explanations to his 'conundrum'.

Posted by

Andrés

at

8:24 PM

|

![]()

Best bet among the oil majors?

Lately, I’ve been doing a bit of researching Big Oil. At first glance, it looks like ExxonMobil –the biggest private energy firm—is doing best, by far. Over the last 12 months its stock has been the top performer in this group and it enjoys the highest valuation by any measure. .

.

Seeing this, I was sure its operating figures must be much better than those of other (such as BP, Shell and Total). But digging deeper, this proved to be very, very false: Exxon has some of the worst figures in the industry.

For instance, take production. According to my calculations, its total oil & gas output has fallen over the last four years (by 1.5%), while BP raised it by 23% and Total by 22%. Reserves, refining and product sales point the same way.

Yes, it’s generating tons of cash for shareholders (nearly 16 billion between dividends and repurchases last year). But this also reflects the fact that it invests much less than its competitors: Exxon’s capital expenditures only took up 30% of its operating cash flow (net income + depreciation), while the other firms invest over 50%.

So, we’re talking about a firm that is basically not growing in real terms, that is probably shortchanging its future by underinvesting and whose stock is pretty expensive.

This makes me wonder whether I’m the only one missing something or most everyone else is in the dark. Well, for what its worth, I believe Total is the best choice in this group, followed by BP.

Posted by

Andrés

at

5:44 PM

|

![]()

Friday, June 03, 2005

Geezers-4-Bonds?

One of the arguments to justify the current low level of long-term bond yields is demography. In the developed world, the number of over 65’s is set to rise dramatically and this group will invest their savings mainly in bonds and other fixed-income instruments.

Sounds like plain common sense. Stocks are an uncertain investment in the short and medium (less than 10 years) and people over 65 years shouldn’t be fooling around with that kind of risk.. However, people don’t always behave or invest rationally.

Take the 2001 Survey of Consumer Finances, carried out by the Federal Reserve. It shows that 21% of families whose head has over 65 years of age have direct holdings of stock, basically the same proportion as the total population. In the over 75 years group, these holdings amount to 27% of all financial assets, the highest proportion of any age group.

Taking only identifiable financial assets (meaning those that are not managed by others, such as mutual funds, retirement funds, life insurance, etc.), it turns out that directly-held stocks represent around 50% of that total in the geezers’ case, a similar proportion to other age groups.

Obviously, this data set has limitations. It’s impossible to break down managed assets by type of investment, so its possible that these holdings will be increasingly oriented to bonds. Nonetheless, the main point stands: old people are not noticeably less risk-averse in their investment choices.

It’s something I’ve seen all too often. I have relatives who still play the market well after retirement age. One was even suckered into investing in tech stocks at the height of the dot com bubble. Greed doesn’t decline with age.

Research seems to back the argument that demography plays a modest role in total and relative demand for different types of assets (see this paper). Actually, if you want to profit from the geezerification of the world, read this study (hint: the secret is in the sectors).

Posted by

Andrés

at

1:04 PM

|

![]()

More on rates

People are seriously confused. While most economists still see long-term intereset rates rising towards 5%, other predict yields as low as 2.5% in the fairly near future. To get a feel for this, be sure to check out this column. As was to be expecteded, history has been dragged into the debate. Many analysts are now arguing that high rates (meaning above 10%) are an aberration, since they were very low before the inflationary 1970's. (Which does not really mean anything, since the world today bears little resemblance to times past.)

This is verily the mystery of the moment. Definitely worth looking into.

P.S. Where do you head for bond info? Look to Bondnheads, naturally.

Posted by

Andrés

at

12:46 AM

|

![]()

Thursday, June 02, 2005

The real interest rate puzzle

Alan Greenspan famously puzzled over why long-term interest rates were so low when the 10-year T bond was yielding well over 4%. Today, its yield stands at 3.9%.

Lots of possible explanations have been offered (check this post). Many are based on short and medium term trends, such as yields driven down by massive foreign purchases of U.S. bonds. This basically implies that rates will rise as soon as these trends run their course, which is anybody’s guess. Another theory emphasizes that Mr. Bond Market (of James Carville fame) sees growth slowing down drastically over the next decade, which in turn will lead to persistent low inflation. That's the position held by Kash.

To clear things up a bit, it’s worth taking a look at what forecasters have to say. This Fed survey presents interesting results. The 2nd quarter forecasts see 10-year T bond rates rising to a bit over 5% in early 2006, with GDP growth slowing to 3.3% next year and inflation averaging around 2.4%.

These figures are actually very similar to the long-term forecasts (for the next ten years) made once a year, in the first quarter. Forecasters see 10-year rates averaging 5% in this period, with GDP growth at 3.3% and inflation of 2.5% over this period.

What does this mean? Once again, there are many possible interpretations. One is that short-term factors are temporarily depressing yields, which will shortly rise to 5%. The obvious problem here is, of course, that they’ve been forecasting a rise to 5% for several years and it ain’t happened.

Given that long-term inflation expectations have held very steady, it seems that the factor that has really driven long-term rates is the real rate. These forecast think it’ll average nearly 2.5% annually, but Treasury inflation-linked bonds have put it at a bit above 1.6%.

This is the real puzzle. Usually, expected long-term real rates have been a tad higher than expected real GDP growth (around 3%). That began to change in 2001, when growth forecasts exceeded expected real bond returns, a gap that has widened dramatically since last year, as it currently stands at a yawning 200 basis points.

Sounds like something has to give: either real rates will rise or long-term growth expectations have to drop.

More on this topic later, but all comments and suggestions are very welcome.

Posted by

Andrés

at

10:54 AM

|

![]()

Wednesday, June 01, 2005

Original name prize

They'd have to give it to Fat Prophets, an independent equity research firm in Australia. I love it.

Posted by

Andrés

at

1:05 PM

|

![]()

Tuesday, May 31, 2005

Keeping the golden faith

As was to be expected, the euro has been hit hard by the results of the French referendum, dropping form around 1.26 US$/EUR to 1.23 in two days. This is likely a knee-jerk reaction, but it’s part of a trend that has been running this year (the US$/EUR rate at the end of last year was 1.36). Obviously, the euro zone’s dismal growth performance, which has driven long term rates to around 3.3%, is the main culprit.

This will cause a lot of pain to that most unusual, even cultish group: gold bugs. The price of gold is negatively correlated to the dollar’s value, so its current strength against the euro (and other currencies) has made it –one of the best investments in the past four years—lose its shine. Its price has fallen 6% this year and 4% over the last 30 days.

However, no matter what trials the markets bring, this group is steadfast in its faith: they, along with many others, including Warren Buffet, still see only damnation for the dollar in the long term (see this example).

Posted by

Andrés

at

10:35 PM

|

![]()

Airlines: So which is it?

On to today's news:

1. Two headlines, seen on the same page:

Airline Industry Says Fuel Costs, Taxes Have Vaporized Profits

Ryanair posts record profit, outlook improves

2. Today's trip to the twilight zone: Six KFC workers die in Karachi violence

Get this: A Sunni extremist group led to al-Qaeda attacks a Shiite mosque in Pakistan. Shiite youths go on a rampage, burning a .....KFC restaurant? So much for my "enemy's enemy is my friend".

Posted by

Andrés

at

10:06 AM

|

![]()

Monday, May 30, 2005

Not quite emerging countries

As a student working for a degree in economics in a large "emerging" country in the early 1990's, I can recall the excitement of seeing wide-ranging liberal reforms being implemented all over the developing world. After surviving the dreary 1980's (aka "The Lost Decade"), it seemed that we were finally starting the dash for growth that would set us on the path for enduring prosperity.

Well, so much for that. In the end, the previous decade ended with a whimper, with crises laying low the nations, such as Argentina and Mexico, that were the toast of the international finance community just a few years back.

The World Bank has just put out a report on economic growth in the 1990's that focusses on the emerging world. I haven't read it in full, but the bits I've looked at are pretty good. In the end, it shows that we still have a lot to learn about what it takes for a country to grow on a sustained basis. It states that in that decade there were 5 major disappointments:

1. The length, depth, and variance across countries of the output loss in the transition from planned to market economies in the former Soviet Union (FSU) and Eastern European countries.

2. The severity and intensity of the international and domestic financial crises that rolled throughEast Asia

3. Argentina’s financial and economic implosion after the collapse of its currency convertibility regime

4. The weakness of the response of growth to reform, especially in Latin America, and the unpopularity of many of the reforms.

5. The continued stagnation in Sub-Saharan Africa, the paucity of success cases there, and the apparent wilting of optimism around the“African Renaissance.”

On the other side of the ledger, the WB states there were 3 pleasant surprises:

1. Bright spots of sustained rapid growth, especially in China, India, and Vietnam, throughout the decade

2. The strong progress in noneconomic indicators of well-being in spite of low growth in some cases.

3. The resilience of the world economy to stresses

One can quibble with the list, but its a fair summary. Needless to say, the main disappointment was that most nations didn't grow as much as initially forecast despite implementing market-friendly reforms. This shows just how hard the business of development actually is.

Posted by

Andrés

at

5:00 PM

|

![]()

Sunday, May 29, 2005

Rock stars for free trade

I’ve never been a big fan of U2, but I certainly admire Bono, its lead singer, for promoting well-known development issues such as HIV and debt relief. After reading this interview in the London Times, I’m even more impressed by his mature outlook. He’s in favor of doing away with rich nations’ agricultural subsidies that hurt exports from developing countries and he even has nice things to say about George Bush and Jesse Helms.

The times, they are a changin’.

Posted by

Andrés

at

3:47 PM

|

![]()

Friday, May 27, 2005

Irreverent weekend morcels

-Recession is a state of mind

Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi disputed Europe's fourth-biggest economy

was in recession, saying Italy was ``full of prosperity and joy,'' citing the

high number of mobile phone users as evidence of the nation's affluence.

``We have a very high percentage of mobile phones and are playboys and send

our girlfriends 10 text messages a day,'' said Berlusconi during a joint news

conference with U.K. Prime Minister Tony Blair. ``Italy is the most beautiful

country in the world and among the richest in the world.''

Read the orginal here.

- "Vision loss is linked to Viagra"

It turns out old men in the 21st century are being told the same thing that young men in the 19th century were constantly reminded of. Queen Victoria must be pleased.

- "Judges Still Reading Khodorkovsky Verdict"

I sure the disgraced former oil tycoon is no saint. But how can a court take 10 days and counting to read a verdict? I'd wager that Saint Peter didn't take that long to read Hitler's verdict.

Posted by

Andrés

at

7:36 PM

|

![]()

The contrarians

The lads over at Morgan Stanley’s Global Economic Forum are in the mood to challenge conventional wisdom today.

First off at bat, Stephen Roach, head economist and high priest of gloom, makes the case for Europe. That's not an easy task, as the Old Continent's list of problems is long: labor rigidity/high unemployment, slow growth, existential angst and growing doubts about the integrationist project, to name a few.

Yet, Roach argues that there is growth, after all, and it’s picking up (albeit to an underwhelming 2% pace in 2006). Reforms are making labor markets more flexible and European corporations are restructuring, increasing productivity through investments in information technology. If the French reject the proposed Euro constitution, the fallout will be very limited (the risks of a deeper Euro rift will rise, but they’re still very low).

I find this argument compelling. Most European nations are in an unsustainable position. You cannot have a generous welfare state with a rapidly aging population and labor market rigidities that keep unemployment high and labor participation low. Something has to give and my bet is that, like it or not, Europeans will realize they have to work more. Combined with high and rising productivity, this will lead to a significant acceleration in growth.

The markets certainly seem to agree: MSCI’s Europe index is up 1.5% in local currency terms since the end of March, when it became clear that the “Non” camp was winning in the French referendum, and is up 5% so far this year. Sure, the euro has fallen from the highs reached at the end of 2004, but it’s still quite a bit above the average level seen last year.

Not to be outdone, Richard Berner brings calm and sense to the housing bubble debate. Like Alan Greenspan, he’s a longtime skeptic of the bubble theory who has recently changed his mind somewhat (to the group that sees ‘froth’ in the market). Berner mentions that prices are not rising as fast as mentioned if house quality and the composition of the market are taken into account and that other metrics, such as the number of houses sold for investment purposes, are biased. As a result, he expects prices to ‘rust’, with perhaps some regional pops. However, he warns that any adverse shocks will mainly affect lenders, not borrowers.

Finally, Andy Xie pours cold water on the notion that the world is on the brink of an outburst of China-related protectionism. As always, he flatly denies that a revaluation of the yuan is in China’s interest and expects its government to ignore U.S. and European pressure to let the exchange rate rise. But Xie also states that the threats to raise trade barriers against Chinese products are hollow: most of these don’t compete directly with U.S. products, U.S. firms capture most of the value chain associated with Chinese imports and, in the end, reducing these imports won’t really cut the huge U.S. trade deficit.

I hope all of them are right.

Posted by

Andrés

at

11:47 AM

|

![]()

Thursday, May 26, 2005

Do you invest as well as your pension fund?

By now, it’s pretty clear that defined-benefit pension plans are an endangered species (see this article). Even relatively healthy firms are switching to defined-contribution plans to transfer investment risk to workers.

Is this a good thing? Sure, if the average Joe was equipped to make smart financial decisions. However, there’s a lot of research that suggest the average investor makes plenty of costly mistakes, such as overlooking costs (this piece provides a nice summary). In that regard, traditional company pension funds, which are usually large and managed professionally, may provide better performance.

I took a look at four large pension funds –two for public sector workers (Calpers and NY State Common), and two company funds (IBM’s and GE’s). Over the last ten years, they averaged a 10.2% annual compound return (the range was very narrow: between 9.9% and 10.6%).

It’s not an extraordinary result. A portfolio made up of Vanguard’s S&P 500 and Total Bond Market index funds, split on a 65-35 per cent basis, would’ve delivered basically the same performance.

Yet, one has to wonder how many people actually earned these returns. My bet is that, on average, they would’ve earned a between one and two percent less, simply from paying higher management fees or from excessive trading. So spare a tear for your traditional pension fund, which in most cases offered workers a decent deal.

Posted by

Andrés

at

3:30 PM

|

![]()

Wednesday, May 25, 2005

Postcards from the housing bubble

· According to a new report, existing home prices are rising at a 15% annual clip and existing home sales rose nearly 7% above year-ago levels. With these figures, even Alan Greenspan, chief housing bubble denier, isn’t sounding too confident nowadays.

· In 2002, 5.6 million existing homes changed hands. With the median home price at 156,000 dollars, the value of residential real estate transactions was roughly 880 billion dollars. Given the figures this year, that number will rise to over 1.5 trillion dollars (figures taken from the NAR).

· The membership of the National Association of Realtors grew 37% between 2001 and 2004 and now stands at 1.1 million. During the same period, non-farm payrolls actually dropped.

· If the bubble does pop, Robert Shiller’s proposal to create house price derivates to enable home owner to hedge against falling values will surely get the attention it deserves.

Posted by

Andrés

at

4:44 PM

|

![]()

Tuesday, May 24, 2005

Culture and economic performance in the Arab world

Moisés Naím argues in this editorial that the success of Arab Americans –they have higher levels of education and income than average—disproves the notion that “Arab culture” is somehow responsible for the relative backwardness of the Middle East. (Thanks to Dan Drezner for the pointer –don’t miss his take and the comments).

On a practical level, Naím’s article has a gaping hole: the national and religious mix of Arab Americans is very different than the ones found in the Middle East and Europe (more details here). He’s comparing apples to oranges.

But it’s worth going back to the culture issue. In this context, it’s such a broad term that it’s virtually meaningless, so one needs to break it down.

If by “culture” we mainly mean “religion”, once can say with certainty that it’s totally irrelevant. The economic performance of many Christian nations is very poor (Latin America, Philippines), while there’s no evidence that Islam per se impedes economic growth (Marginal Revolution has a lot on this topic, check out this post and this one).

But if we include such aspects as institutions, politics, etc. in “culture”, it’s impossible to deny that they have an impact on a nation’s prosperity. In this regard, most Middle Eastern nations do have one thing in common: they were part of the Ottoman empire for centuries. While I’m no expert on this topic, it’s fairly clear that the Ottoman’s were good warriors but very incompetent economic managers (more on this topic here) who didn’t put in place a decent institutional framework.

Posted by

Andrés

at

3:39 PM

|

![]()

A currency mystery solved

Bombarded as we are every day by articles on China’s currency dilemma, I couldn’t help but wonder what that currency is called. Some pieces refer to it as the renminbi, while others refer to it as the yuan.

So which is it? Actually, both are correct. According to this explanation, renminbi can be literally translated as “people’s currency”, while “yuan” is the main unit of measurement. Hence, in banknotes the amounts are expressed in yuan (or

In the West, we don’t distinguish between both terms (it’d be awkward to say “the chocolate bar costs one United States currency unit”), but that doesn’t mean it can’t be done. I, for one, will stick to yuan.

Posted by

Andrés

at

12:35 PM

|

![]()

Monday, May 23, 2005

Quest for yield: Peso bonds

With real yields on U.S. bills and bonds perilously close to cero, investors are leaving no stone unturned in the search for decent returns.

This is leading many to markets they would’ve never heard of, let alone invested in, not long ago. For example, consider the case of Mexican government bonds issued in pesos. Believe it or not, they’re a novelty: before 2000, the only paper issued matured in one year or less. Now, you can even get 20 year bonds.

If that sounds like your idea of playing Russian roulette, there are an awful lot of candidates willing to give it a shot for yields that currently average a grand total of …..10% (check them out in Banco de México’s site). Currently, foreigners own around 20% of the total amount outstanding; a year ago, that proportion stood at 6%, even though the spread between U.S. and Mexican Bonds hasn’t risen much.

How crazy is this bet? It’s hard to tell. Your main enemy is, obviously, exchange rate risk. The yield in dollars of this investment will, basically, amount to your gross yield in pesos minus the peso’s accumulated depreciation against the dollar. So, if you buy for keeps, to earn more than you would if you purchased an equivalent U.S. bond, you need the peso to depreciate less than 5% per year against the dollar.

Forecasting exchange rates is a dangerous game. The peso has floated only since 1995 and it spent the next few years recovering from the Tequila crisis. Yet, over the last five years, it has only fallen on average around 3% a year against the dollar. This despite the lackluster performance of the Mexican economy (low growth, but stable interest rates and inflation). So, if this keeps up, you’d earn between 6% and 7% in dollars, a bit more than you’d get investing in Mexican bonds issued in dollars. However, if you’re a Mexico bull –an admittedly rare species, but apparently gaining in numbers—and believe the peso will stay stable or even gain a bit against the greenback, a 10% yield in pesos looks mighty good.

What do Mexicans think? With an old-school populist leading the race for the 2006 elections, they’re keeping an eye on politics, fastening the hatches for likely turbulence and praying that a divided Congress and a formally independent central bank will hold back the barbarians at the gate.

Posted by

Andrés

at

5:54 PM

|

![]()

Friday, May 20, 2005

The Maestro on energy

Whatever you may think of Alan Greenspan’s record as head of the Federal Reserve, he is a very bright fellow. I always learn something new every time I read one of his speeches. His most recent talk on energy markets is not an exception.

For example, it turns out that the 200 million light vehicles in the U.S. consume 11% of the world’s oil output.

But it’s not all trivia. Greenspan lays the blame on the current surge in oil prices on underinvestment in producing countries and the growing weight of nations with energy-intensive economies, such as China.

Interestingly, he pays at least as much attention to natural gas as to oil (gas is virtually ignored in the mainstream press). In the last few years, gas prices have risen even more than oil prices, although in a thermal equivalent basis they’re about $10 lower, and they’ve been much more volatile. The problem here is that demand has grown while US and Canadian supplies have lagged. Imports are growing, but the infrastructure for LNG has not been coming on line fast enough.

However, he suggests that once imports rise, the price of natural gas may fall from around $6 per million BTU to around $3 per million BTU. In oil-equivalent terms, that’s around 17 dollars per barrel.

He also describes technical advances that allow gases to be converted into fuel liquids (such as diesel). This opens the possibility for natural gas and oil prices to converge. Currently, long-term oil futures (for delivery in 5 years of more) trade at $46 per barrel, while similar contracts for natural gas go for the equivalent of $34 per barrel, so there’s hope that we’ve seen the worst in terms of price increases.

In the end, it’s a pretty optimistic speech with a simple message: never underestimate the power of technology and price signals.

Posted by

Andrés

at

1:15 PM

|

![]()

Thursday, May 19, 2005

Trading around the world

Yesterday I talked about the amazing rise in stock trading activity in the U.S., measured by the number of transactions in the two main markets (NYSE and Nasdaq). But how does America compare with other nations?

Last year, there were around 6.4 trades per person in the U.S. This is pretty high compared to most developed countries. For example, in Canada there were only 1.1 trades per person, while in the U.K. and Germany there were only 0.9 trades per inhabitant.

But Americans’ love of trading doesn’t hold a candle next to the Taiwanese, who carried out 7.7 trades per person last year. In fact, most East Asian nations have very high levels of trading: Hong Kong registers 5.5 trades per person, while Korea’s level stands at 2.9 ( no data on Japan though).

I don’t know why the differences are so big. Maybe it’s a cultural thing: Europe’s financial culture is much more bank-centered, while the Chinese appetite for risk is legendary.

(Trading data is taken from this site, while population data can be found at the Census site).

Posted by

Andrés

at

9:52 AM

|

![]()

Wednesday, May 18, 2005

Day trade nation

Five years ago, trading stocks was the new national pastime. One would imagine that the severe market downturn of 2001-2002 extinguished the desire of gaining instant riches by playing the markets. Sounds reasonable, but it’s false: the passion for trading still rages throughout the land.

Just take a look at the data. According to data from the International Federation of Stock Exchanges, the number of equity trades in the U.S. (including the NYSE and Nasdaq) rose 310% between 2004 and 1999. To put this in perspective, in 1999 there were 1.6 equity trades per person in the U.S., a number that rose to 6 last year. In other developed nations, the avaerage number of trades per person is usually less than one.

It's also worth pointing out that the average value per trade fell dramatically: from 42,000 dollars to just over 10,000.

Now, event though the ease and low costs of online trading have surely led to a large increase in the number of individual investors actively involved in the markets, it is also possible that other trends, such as the explosion in hedge funds, have contributed to the huge increase in trading.

What is pretty certain is that much of this trading is wasteful. Any number of studies have shown that transaction costs are the nemesis of investors. The math is well-known: on average, individual investors will obtain gross returns equal to the market average (say, the return on the S&P 500), but trading costs push the net returns significantly lower. If memory serves me right, most will lose around two percentage points annually by trading too much.

Posted by

Andrés

at

11:13 AM

|

![]()

Bulls in the china shop

That’s a very adequate metaphor for U.S. policy towards China, as described in the previous post. Apropos, here is Brad Setser’s take on this issue, a must read that lays out well the sheer complexity of China’s currency dilemma.

If you feel like you need to grasp the big picture, don’t miss Bill Gross’s (PIMCO's Grand Master of Bonds) very accessible description of the main issues facing the U.S. and the global economy.

Posted by

Andrés

at

10:24 AM

|

![]()

Tuesday, May 17, 2005

The China factor

What a strange day in the markets. It certainly began badly: higher than expected wholesale inflation and lower than expected industrial production figures for April (as to these, weakness was concentrated in the automobile sector). Yet, in the end the broad indices managed to rise nearly 1%.

Most commentators stated that a Treasury Department report to Congress on exchange rates and trade saved the day. This report warned China that unless it takes steps soon to make its exchange rate more “flexible” (that is, let it rise), it would be branded as a “currency manipulator”, a designation that would give free rein to the Congressional demons of protectionism

So why is this good news? Well, the dopiest reporters argued that American stocks rose because these warnings would be heeded and American firms will eventually face less Chinese competition. Smarter hacks said that the positive reaction reflected a collective sigh of relief, since apparently some talking heads had expected the Treasury to accuse the Chinese of manipulation in this report.

I know, it doesn’t make much sense either. My guess is that stocks rose in sympathy with good earnings numbers from H P and Home Depot, among others.

As to the China factor, some experts argue that letting the yuan rise would be a good idea, since it’d be a necessary step for correcting the current unbalanced state of the world economy (Brad Setser is in this camp, broadly speaking). Other fear it will plunge China –and probably other East Asian economies--into a nasty Japanese-style deflationary spiral, with negative consequences for the world economy (Andy Xie of Morgan Stanley more or less supports this view).

In other words, no one really knows, but everyone agrees it will have a big impact. Oh, and by the way, is it really a good idea to push around the face-saving, prickly, Chinese who happen to finance a rather large chunk of government spending in the U.S.?

Posted by

Andrés

at

6:52 PM

|

![]()

The absurdity of competitiveness

What is it about our love for ranking nations according to their “competitiveness”? To me, these lists, such as the one published by the Word Economic Forum (WEF), seem totally useless. Basically, the rankings are nearly identical to an ordered list of income per person. Which is rather tautological: the richer you are, the more competitive you are and vice versa. Duh.

Part of the problem, of course, is that “competitiveness” has many meanings, as this excellent article explains. Yet, even if we agreed upon on a specific definition, it is a flawed concept. John Kay tells it like it is:

Interest in national competitiveness is an extension of interest in the competitiveness of companies. Competitive businesses are able to offer goods or services more attractive than those of their rivals through lower costs or better products.

But the analogy between individual businesses and national economies doesn't quite hold.Companies that are not competitive disappear. Countries that are not competitive don't. These nations still need to import, and their exchange rate falls until they become competitive again. Every country that trades internationally is competitive in some areas - the things it exports - and uncompetitive in others - those it imports. This principle of comparative advantage has been a foundation of economic analysis for 200 years.

Posted by

Andrés

at

10:47 AM

|

![]()

"Flying Salmon Sighted Over Washington"

Give the gals over at Tamara Wilson Public Relations a cigar for coming up with that headline for this prosaic press release.

Posted by

Andrés

at

9:59 AM

|

![]()

Friday, May 13, 2005

Investors never learn

Thanks to Mahalanobis for providing a link to Burton Malkiel’s latest piece on market efficiency and fund investing. As always, he makes the compelling case that most people who invest in stocks should stick to boring-but-cheap index funds. Yet, as index-fund pioneer John Bogle points out here, their market share in the stock fund segment stands at less than 20%.

People are just as overconfident about picking winning funds as they are about selecting above-average stocks, with equally lousy results.

Posted by

Andrés

at

6:10 PM

|

![]()

Thursday, May 12, 2005

Alternative market recap: Oil beats Wal-Mart

I frequently chastise the financial press for trying to explain away the stock market’s random day-to-day fluctuations by latching to an eye-catching event that probably has little to do with what happened.

Today offers a great example. Stocks fell across the board, though the drop was unremarkable (about 1%). There were three important pieces of news: oil prices dropped sharply for the second day in a row amid reports of slower than expected demand growth and high inventories, U.S. retail sales rose strongly in April and Wal-Mart reported disappointing first quarter earnings, in addition to warning that this quarter’s results would also be weak due to high gas prices.

Reporters spun it this way: Falling oil prices in April helped boost retail sales much more than expected, yet these two pieces of good news were offset by Wal-Mart’s earnings miss and its fairly gloomy forecast for this quarter, not to be taken lightly coming from the world’s largest retailer.

However, why should Wal-Mart be so pessimistic given that oil prices are falling? Doesn’t less expensive energy help consumer spending? Needless to say, reporters got very confused (see this example of tortured logic). In the end, since stocks fell, they mostly blamed the largest and best-known target: Wal-Mart.

Actually, today’s performance can be explained quite easily. The energy sector represents arount 10% of the S&P 500 and today it fell around 4% on average. This alone explains about half the drop. Most of the rest can be accounted by the retreat in financial sector stocks (around 1% today, but they make up more than 20% of the S&P 500), probably attributable to recent market jitters concerning hedge funds

And Wal-Mart? Yes, it’s big and its announcement didn’t help. But keep in mind that the consumer staples sector --which has a similar weight compared to the energy sector--to which it belongs actually fell only 0.5% today according to S&P’s data, much less than the market as a whole.

In any case, one shouldn’t read too much into one day’s figures. Stocks fluctuate for any number of reasons day after day. But if you do keep track of these things, always check broad sector trends, which are always more representative than extrapolations based on the performance of one or two stocks. Standard & Poor’s provides these figures on a daily basis.

Posted by

Andrés

at

5:22 PM

|

![]()

Organized labor is dead, long live organized labor!

What do today’s failing firms, such as GM, Ford, UAL and Delta have in common? Mainly, they’ve been unable to adapt to changing market conditions, unlike their more nimble rivals (Toyota in autos, Southwest in air travel).

This brings me to another shared trait: these firms are bastions of union power. While no one can deny that they’ve been badly managed for a very long time, organized labor has also played a big role in their demise. It forced the firms them to employ too many workers, stick to obsolete and rigid work practices, concede excessive long-term benefits in the good times and made it very difficult to close unprofitable operations (plants, routes, etc.). Last but not least, management and labor spend so much time bickering about issues like pensions that the firms’ main business is neglected.

Needless to say, their successful rivals are mainly non-unionized or face pliant Japanese-style labor organizations.

When these ships sink, as they surely will (at least in their present form), organized labor’s long decline will be nearly complete. Sure, it’ll hang on for a while in the economy’s non-competitive corners, such as government, but in the private sector it’ll be basically extinct.

Like the medieval guilds that preceded them, unions were well-suited to a certain environment: growing, regulated economies where production was increasingly carried out in workplaces with rigidly defined repetitive processes. Obviously, this no longer describes our world, where repetitive labor is increasingly automated, changing tastes and conditions require flexibility and competition is ever-increasing.

As always, most workers do have an interest in banding together to negotiate better terms for themselves, so the question now is not whether unions will be replaced but what will substitute them.

My guess is that a new type of labor organization will come along, one that provides services to the individual worker, rather than the firm or industry unions we know today. These new unions will provide many things that neither the market nor the government do well, such as training, job search assistance, unemployment insurance, career change services, legal advice, infant care, etc. Firms will be left alone to do what they will, but they’ll have to meet minimum standards and comply with contractual obligations with regard to workers. Otherwise, they’ll face strong legal action and the new unions will be able to pressure firms by withholding qualified labor.

These new organizations will provide benefits to society as a whole. They’ll make it easier to retrain and reemploy workers displaced by changing tastes and international competition, thus reducing resistance to socially beneficial policies such as free trade. In addition, they could help workers take advantage of existing but underused benefits, such as tax-free retirement accounts. They could even play a positive role in matters such as corporate governance and health care (giving their members better bargaining power vis a vis providers).

Well, only time will tell. But at least my utopian future unions sound like a an attractive alternative to the Teamsters and their like.

Posted by

Andrés

at

2:26 PM

|

![]()

Wednesday, May 11, 2005

The economist as freak

Recently, Bryan Caplan of Econolog mused about why people tend to dislike and ignore economists. In the end, he argued that dismal scientists should forget about being nice. Instead, they should be blunt, telling people how things really work as explained by the principles of classical economics. Call it the Larry Summers approach.

Mr. Caplan is right about how ecomists are perceived. Nonetheless, he simply misses the point. People mistrust economists because, unlike them, they don't constantly look at the world through the prism of maximization (at least conciously). This post by Caplan nicely illustrates this point:

I wear shorts about 10 months per year, and I live near Washington DC.

Judging from the number of funny looks I get, and the number of times perfect

strangers stare at me and ask "Aren't you cold?," my behavior is puzzling at

best.The silly explanation is that I'm from California. But that should

make me more sensitive to cold, not less! The real answer, naturally, is that