Well, it's actually from yesterdary, but never mind. As seen on FT.com: "Wall Street bounces back after GM disappointment"

Ask yourself what is wrong with that statement (yes, GM did report below the consensus earnings forecast). If your answered that it's impossible for GM to dissapoint, no matter what the consensus expectations are, go buy yourself a cigar. After all, it has lost market share for nearly as long as I've been alive. It's management, who has tried any number of strategies to turn things around (except maybe human sacrifice to ask the gods to jinx Toyota), gives new meaning to "hapless". It'd be broke if it weren't for America's inexplicable love of big, ugly trucks.

In related news, it takes a brave (or foolhardy) soul to forsake a cushy Wall Street post to join GM. Wild conspiracy theory: he knows the current management team will probably be run out of town sooner rather than later by Kerkorian and could emerge as a credible candidate for a top job.

Thursday, July 21, 2005

Dumb headline of the day

Posted by

Andrés

at

7:13 PM

|

![]()

Friday, July 01, 2005

The U.S. as a gigantic hedge fund

Yesterday, the Bureau of Economic Analysis reported that the net international position of the U.S. –which is the amount of U.S.-owned assets abroad minus the amount of U.S. assets held by foreigners--was minus 2,484.2 billion dollars at yearend 2004, higher than the minus 2,156.7 billion level in 2003 (figures at market value).

At the end of 2004, Americans owned nearly 10 trillion dollars worth of foreign assets, while foreigners owned U.S. assets worth 12.5 trillion dollars.

This comes as no surprise. After all, the U.S. has been running current account deficits (i.e. has been a net barrower) for a long time.

The real shock comes when one sees the returns earned by these assets held by each party. According to the latest balance of payments data, the income earned by U.S.-owned assets in 2004 was equivalent to 4.5% of yearend assets at market value, while foreigner earned just 3.2% on their American assets.

That’s not all. The BEA breaks down the changes in value of assets price appreciation, foreign exchange gains and others by source (price appreciation, foreign exchange gains and others). Assets owned by Americans appreciated 5% in 2004 (before taking into account foreign exchange gains/losses and with yearend 2003 values as the base level). Foreign-owned U.S. assets gained only 2.7%.

As a result, U.S.-held assets gained 9.7% (price appreciation + income), while foreigners gained 5.8%. Obviously, by taking yearend 2003 assets, these returns are somewhat overstated, but still indicative.

Why are U.S.-owned assets more profitable? The answer composition of the assets. In first place, 97% of the assets held by Americans are privately held, a percentage that falls to 84% in the case of foreigners (the remaining 16% is held by governments and official institutions such as central banks). One would expect privately held assets to yield higher returns.

But there are significant differences even in private assets. In the case of U.S.-owned assets, holdings of equity, either as foreign direct investment or foreign stocks, were 60% of the total in 2004, while foreigners held only 45% of their private assets in these two categories. In general, equities should also yield higher returns, although their risk is also higher.

So, in a way, the U.S. borrows short to lend/finance long. If it weren’t for the sheer scale of its borrowing, it’s actually a pretty smart strategy that plays to America’s comparative advantage in finance.

Brad DeLong links to a study that takes a deeper look at this phenomenon. Interestingly, the U.S. earns more even within specific asset classes.

Posted by

Andrés

at

4:02 PM

|

![]()

Wednesday, June 29, 2005

Climate change is for real

As a science dunce who has trouble telling his electrons form his photons, I'm not qualified to disucuss the debate concerning global warming. But when insurers --more concerned with odds rather than politics--express their worries in public, it's a sure sign that it's for real.

Posted by

Andrés

at

9:11 AM

|

![]()

Friday, June 24, 2005

A very vicious circle

The Buttonwood column at The Economist lays it out very cleary.

Companies and asset managers have tended to take a laid-back approach to pension underfunding, relying on the markets to right things as they often have before. What is worrying about the latest numbers is that we are seeing them towards the end of a period of strong economic growth and corporate profitability, neither of which is likely to continue. John Mauldin, an investment consultant, calculated in a recent column that total portfolio returns over the next ten years were likely to be around 5%, far less than the 8-9% projected by most funds. He reckoned that the total shortfall in America could be somewhere between $500 billion and $750 billion. And that is without counting companies’ promises to provide health care to employees and retired workers. Nicholas Colas at Rochdale Research, an independent firm, calls these obligations a bigger problem than pensions because they are neither funded nor insured.

There are a couple of weird circularities here. Most of the burden of filling these gaps will fall on the companies themselves, which will depress their profits. That, in turn, will depress share prices, which will make it harder to achieve adequate investment returns. And if asset managers turn en masse to bonds with long maturities to match their assets and liabilities more precisely, which is necessary especially for older plans, that will raise bond prices, depress bond yields and increase the present value of assets they must hold—again, widening the pensions gap. They could, of course, look to other asset classes that pay higher or “absolute” returns (hedge funds of funds, private equity, property) and many are doing so. But “alternative” assets do not typically account for more than one-tenth of the total portfolio, in part because they are labour-intensive to manage.

A the column spells out, there is a huge funding gap and no one –firms, workers, taxpayers, shareholders—wants to end up holding this hot potato.

I’m not an expert on this subject, but I believe it’s likely that that the burden will fall on the weakest link: shareholders, who as always have the largest collective action problem. How so? Well, one solution will be to “capitalize” the pension obligations by swapping the funding obligations for shares. This basically implies, for example, that the United Auto Workers will end up owning General Motors and Ford.

Maybe this is a non-starter under conditions in the United States. But I believe this “solution” is feasible in may contexts. For example, most state-owned firms in emerging economies have pension deficits that make the funding gap in the U.S. or other developed nations look like child’s play. Governments are often very eager to privatize those firms to avoid the inevitable rescue package that will bust the treasury, but unions are adamantly opposed. So, in the end, the likeliest bargain will be to transfer ownership to the workers.

Posted by

Andrés

at

11:05 AM

|

![]()

Tuesday, June 21, 2005

Oil gone wild

It’s rather remarkable how the markets have reacted to oil at nearly 60 dollars per barrel, just four weeks after dropping to 47 dollars per barrel: stock prices have risen on average and bond yields have stayed put.

The good news is that high and rising oil prices are usually a sign of strong growth in the world economy, which of course is most welcome.

The bad news is that we’re entering dangerous territory and no one seems to know what’s really going on.

Some analysts, such as Andy Xie over at Morgan Stanley, explain away the jump in oil prices as the consequence of rampant “speculation”. They argue that slower growth and the rising output of petroleum substitutes will cause a dramatic collapse in oil prices in the near future.

Obviously, “speculation” is an oft misused and abused word, but there’s some evidence to back this point of view. For one, it’s hard to reconcile oil at record price levels with inventories at 5-year highs in the U.S.. And let’s not forget that neither the demand or supply outlook has changed over the last few weeks.

Yet, the fact remains that spare capacity is low and demand in the U.S. and the Asia Pacific region is still very strong. (By the way, I don’t buy the capacity-constraints-at-refineries argument: heavy crudes have risen as much in value as light crudes).

Things get even weirder at a more fundamental level. While many insist that oil production will keep on rising for quite a while, the “peak oil” movement loudly argues otherwise.

Regardless of who’s right, one has to wonder what impact energy prices at this level will have on the world economy. Sure, it’s dodged the bullet so far, but it’s possible if that the price of oil crosses-a certain threshold—obviously unknown—the impact will be severe.

Where does that leave mere mortals like me? Well, if I have to trust anyone, it’d be the price mechanism, which is signaling strong demand and high prices for the foreseeable future. However, for investment purposes, I’d use fairly conservative assumptions: my long-term guess is that oil will average around 40 dollars per barrel over the next few years. And, yes, high prices will take their toll on output over the next few months.

Posted by

Andrés

at

2:48 PM

|

![]()

Thursday, June 16, 2005

Bin travelin'

Sorry for not posting, but I've been travelling a bit in the U.S. on business. As always, it's a pleasure to be here (Southern California), although the weather has not been very cooperative (cloudy and cool).

With a patchy net connection, I've indulged in watching local TV. All the advertising by lawyers never ceases to amaze me or any other foreigner for that matter. According to this article, it totals around 500 million a year, most of it spent on television. That's about 499 million more than lawyers spend in the rest of the world.

And speaking of being overlawyered, on a visit to a residential compound I asked an employee what kind of people lived there (I was thinking along the lines of singles/married couples with kids). With a straight face, he stated that he couldn't answer for legal reasons (apparently some sort of non-discrimination statute).

Yet, you can find very, very detailed data that breaks down enrollment by ethnic/racial group and their respective standarized test scores.

So, you can't ask about what neighbors you'll have (something you can easily find out just by hanging out a while), but you can precisely tell who your children will study with. That's weird and wonderful America for you.

Posted by

Andrés

at

3:32 AM

|

![]()

Saturday, June 11, 2005

Anarchy and cell phones

The emerging nations of this world are a strange mixture of pockets of modernity and large areas of abject poverty. This sets the stage for some truly amazing, heartbreaking stories. Take this one from the latest issue of The Economist:

Veronique, an office worker, was separated from her daughter by the war. When peace broke out, she booked an aeroplane ticket for her (penniless) girl to rejoin her. But before the daughter could board the plane, she was detained. Her yellow fever vaccination card had been stamped by rebel health authorities, and so was invalid, the officials tut-tutted. Alas, she had no money for a bribe.

But Veronique was able to send her the equivalent of cash by mobile telephone. She bought $20 worth of telephone cards. These give you a code number which you key into your phone and thereby “recharge” it with pre-paid airtime. Veronique called the obstructive officials and gave them her code numbers to recharge their own mobile phones. It took only minutes to send her bribe across the country—faster than a bank transfer, which would in any case have been impossible, since there is no proper banking system.

That's Congo. Private cellphone networks and private airlines work because the landlines do not and the bush has eaten the roads. Public servants serve mostly to make life difficult for the public, in the hope of squeezing some cash out of them. Congo is a police state, but without the benefits. The police have unchecked powers, but provide little security. Your correspondent needed three separate permits to visit the railway station in Kinshasa, where he was stopped and questioned six times in 45 minutes. Yet he found that all the seats, windows and light fixtures had been stolen from the trains.

If only Joseph Conrad were alive today.

The Congo is obviously an extreme, tragic case. But even for more "developed" emerging nations, true prosperity and stability remain elusive, even nearly 200 years after independence, as is the case of Latin America. Just look at Bolivia. I don't want to be a pessimist, but even well-meaning initiatives such as debt relief are not going to make a real difference unless the politics of the these countries can be fixed.

Posted by

Andrés

at

6:43 PM

|

![]()

Thursday, June 09, 2005

Forecasting stocks

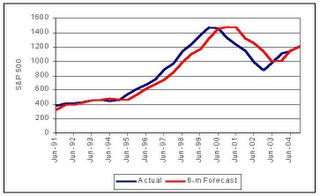

Yesterday I posted about the results of the Livingston Survey regarding the economic outlook for the U.S. I was surprised to find that the survey participants are also asked to forecast for the level of the S&P 500 for periods ranging up to 24 months ahead.

So, are economists any better than others at forecasting the stock market? Not really.

Due to data comparison problems, I only took a look at 6 and 12-month forecasts from 1990 onwards. The results are pretty clear, as can be seen in this graph:

Economists commit the same sin as the average investor: their forecasts are basically just extrapolations of recent trends. And even in periods where there were clear trends, these extrapolations were wide off the mark. For example, the level of stock prices was consistently underestimated in the 1990’s (not surprising given the bubble and their knowledge of long-term trends).

On average, there was a +/- 15% error margin for 6-month forecasts, which rose to +/- 20% in the 12–month horizon.

If you had trusted them to manage your money, say by allocating between stocks and bonds, you would’ve had terrible results. That’s perhaps the reason that on Wall Street economists are mostly confined to the safety of research departments.

Posted by

Andrés

at

12:09 PM

|

![]()

Wednesday, June 08, 2005

Want to know what economists are thinking?

Just go and check out the results of the Livingston Survey, the oldest continous survey of U.S. economic forecasts (in business since 1946). Reuters has a good summary here.

The results are very similar to the ones I described a few days ago (based on a Federal Reserve survey): growth will stay over 3% and inflation will average 2.5% over the next ten years. Thus, economists see long-term interest rates rising to 5% as early as next year.

Needless to say, the bond market begs to differ. Only time will tell who's right.

Posted by

Andrés

at

7:32 PM

|

![]()

Of spreads and stocks

As if the long-term rate conundrum weren’t enough, I’m afraid we have another puzzle on our hands, this time related to the behavior of bond spreads and stock prices.

Spreads –in this case the difference between the yields of Baa-rated bonds and 10-year Treasuries--are usually high during recessions or periods of slow growth and tend to fall in more prosperous times. They aren’t correlated with the level of rates, but they do show a strong negative response to changes in rates: that is, spreads rise when rates fall and vice versa. The cause is clear: falling rates imply lower expected inflation, which in turn reflects slower growth in the economy and a lower earnings performance in firms.

The following graph shows normalized (i.e. long term average =1) 10-year yields and Baa spreads.

img src="http://photos1.blogger.com/img/31/6194/320/spreads.jpg">.

A few brief observations:

· After 2000, spreads went wild, reaching never before seen heights despite the fact that the 2001 recession was pretty mild. This probably reflects structurally higher leverage.

· Despite robust economic growth in 2004/2005, spreads are still pretty high relative to the long run average.

· As was to be expected, spreads have risen sharply in the past few weeks, in tandem with falling long-term rates.

· Spreads will only fall to long-term average levels if rates rise towards 5%.

The central message here is that the recent fall in rates is not good news, as it signals a weaker economy that will lower credit quality and raise the level of financial risk.

However, it’s worth noting that stocks in the U.S. have posted gains in the last two months, a period in which spreads rose sharply. Needless to say, this is contradictory: stocks usually move in the opposite direction of spreads.

So who’s right? I honestly wished I did. The only thing I do know is that we live in very uncertain times when traditional correlations are not working as expected. Hence, I’d have a very cautious investment policy. Cash anyone?

Posted by

Andrés

at

11:32 AM

|

![]()